Hawaiian Islands

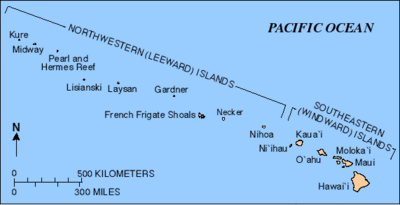

The Hawaiian Islands (Hawaiian: Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, numerous smaller islets, and undersea seamounts in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some 1,500 miles (2,400 km) from the island of Hawaiʻi in the south to northernmost Kure Atoll (the northwesternmost island in Hawaii is Green Island, which is joined to the Kure Atoll). Excluding Midway, which is an unincorporated territory of the United States, the Hawaiian Islands form the U.S. state of Hawaii. Once known as the "Sandwich Islands", the archipelago now takes its name from the largest island in the cluster.

The islands are the exposed peaks of a great undersea mountain range known as the Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain, formed by volcanic activity over a hotspot in the Earth's mantle. At about 1,860 miles (3,000 km) from the nearest continent, the Hawaiian Island archipelago is the most isolated grouping of islands on earth.[1]

Contents |

Islands and reefs

Captain James Cook visited the islands on January 18, 1778 and named them the "Sandwich Islands" in honor of John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, who was one of his sponsors as the First Lord of the Admiralty.[2]

The Hawaiian Islands have a total land area of 6,423.4 square miles (16,636.5 km2). Except for Midway, which is an unincorporated territory of the United States, these islands and islets are administered as the state of Hawaii — the 50th state of the United States of America.

Main islands

The eight main Hawaiian islands (also known as the Hawaiian Windward Islands) are listed here from east to west. All except Kahoʻolawe are inhabited.

| Island | Nickname | Location | Area | Area rank |

Highest point | Elevation | Population (as of 2000) |

Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hawaiʻi[3] | The Big Island | 4,028.0 sq mi (10,432.5 km2) | 1st | Mauna Kea | 13,796 ft (4,205 m) | 148,677 | 37/sq mi (14/km²) | |

| Maui[4] | The Valley Isle | 727.2 sq mi (1,883.4 km2) | 2nd | Haleakalā | 10,023 ft (3,055 m) | 117,644 | 162/sq mi (62/km²) | |

| Kahoʻolawe[5] | The Target Isle | 44.6 sq mi (115.5 km2) | 8th | Puʻu Moaulanui | 1,483 ft (452 m) | 0 | 0 | |

| Lānaʻi[6] | The Pineapple Isle | 140.5 sq mi (363.9 km2) | 6th | Lānaʻihale | 3,366 ft (1,026 m) | 3,193 | 23/sq. mi. (9/km²) | |

| Molokaʻi[7] | The Friendly Isle | 260.0 sq mi (673.4 km2) | 5th | Kamakou | 4,961 ft (1,512 m) | 7,404 | 28/sq mi (11/km²) | |

| Oʻahu[8] | The Gathering Place | 596.7 sq mi (1,545.4 km2) | 3rd | Mount Kaʻala | 4,003 ft (1,220 m) | 876,151 | 1,468/sq mi (567/km²) | |

| Kauaʻi[9] | The Garden Isle | 552.3 sq mi (1,430.5 km2) | 4th | Kawaikini | 5,243 ft (1,598 m) | 58,303 | 106/sq mi (41/km²) | |

| Niʻihau[10] | The Forbidden Isle | 69.5 sq mi (180.0 km2) | 7th | Mount Pānīʻau | 1,250 ft (381 m) | 160 | 2/sq mi (1/km²) |

Smaller islands, atolls, reefs

Smaller islands, atolls, and reefs (all west of Niʻihau and uninhabited) form the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, or Hawaiian Leeward Islands:

- Nihoa (Mokumana)

- Necker (Mokumanamana)

- French Frigate Shoals (Mokupāpapa)

- Gardner Pinnacles (Pūhāhonu)

- Maro Reef (Nalukākala)

- Laysan (Kauō)

- Lisianski Island (Papaʻāpoho)

- Pearl and Hermes Atoll (Holoikauaua)

- Midway Atoll (Pihemanu) (temporary residential facilities)

- Kure Atoll (Kānemilohaʻi)

Islets

The state of Hawaii counts 137 "islands" in the Hawaiian chain, and the Midway Islands.[11] This number includes all minor islands and islets offshore of the main islands (listed above) and individual islets in each atoll. These are just a few:

- Ford Island (Mokuʻumeʻume)

- Lehua

- Kaʻula

- Kaohikaipu

- Manana

- Mōkōlea Rock

- Nā Mokulua

- Molokini

- Mokoliʻi

- Moku Manu

- Moku Ola (Coconut Island, Hawaii)

- Moku o Loʻe (Coconut Island, Oahu)

- Sand Island

- Grass Island

Geology

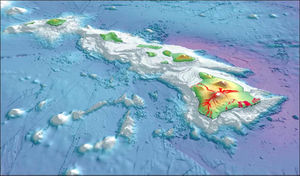

The chain of islands or archipelago formed as the Pacific plate moved slowly northwestward over a hotspot in the Earth's mantle at about 32 miles (51 km) per million years. Hence the islands in the northwest of the archipelago are older and typically smaller, due to longer exposure to erosion. The only active volcanism in the last 200 years has been on the southeastern island, Hawaiʻi, and on the submerged but growing volcano at the extreme southeast, Loʻihi. The Hawaiian Volcano Observatory of the U. S. Geological Survey documents recent volcanic activity and provides images and interpretations of the volcanism.

Almost all magma created in the hotspot has the composition of basalt, and so the Hawaiian volcanoes are constructed almost entirely of this igneous rock and its coarse-grained equivalents, gabbro and diabase. A few igneous rock types with compositions unlike basalt, such as nephelinite, do occur on these islands but are extremely rare. The majority of eruptions in Hawaiʻi are Hawaiian-type eruptions because basaltic magma is relatively fluid compared with magmas typically involved in more explosive eruptions, such as the andesitic magmas that produce some of the spectacular and dangerous eruptions around the margins of the Pacific basin.

Hawaiʻi island (the Big Island) is the largest and youngest island in the chain, built from five volcanoes. Mauna Loa, comprising over half of the Big Island, is the largest shield volcano on the Earth. The measurement from sea level to summit is more than 2.5 miles (4 km), from sea level to sea floor about 3.1 miles (5 km).[12]

See also: List of Hawaii rivers

Earthquakes

The Hawaiian Islands have many earthquakes, generally, caused by volcanic activity. Most of the early earthquake monitoring took place in Hilo, by missionaries Titus Coan, Sarah J. Lyman and her family. From 1833 to 1896, approximately 4 or 5 earthquakes were reported per year.[13]

Hawaii accounted for 7.3% of the United States' reported earthquakes with a magnitude 3.5 or greater from 1974 to 2003, with a total 1533 earthquakes. Hawaii ranked as the state with the third most earthquakes over this time period, after Alaska and California.[14]

On Sunday, October 15, 2006, there was an earthquake with a magnitude of 6.7, off the northwest coast of the island of Hawaii, near the Kona area of the big island. The initial earthquake was followed approximately five minutes later by a magnitude 5.7 aftershock. Minor-to-moderate damage was reported on most of the Big Island. Several major roadways became impassable from rock slides, and effects were felt as far away as Honolulu, Oahu, nearly 150 miles (240 km) from the epicenter. Power outages lasted for several hours to whole days. Several water mains ruptured. No deaths or life-threatening injuries were reported.

Earthquakes are monitored by the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory run by the USGS.

Tsunamis

The Hawaiian Islands are subject to tsunamis, great waves that strike the shore. Tsunamis are most often caused by earthquakes somewhere in the Pacific. The waves produced by the earthquakes travel at speeds of 400–500 miles per hour and can affect coastal regions thousands of miles away.

Tsunamis may also initiate in the Hawaiian Islands. Explosive volcanic activity can cause tsunamis. The island of Molokaʻi had a catastrophic collapse or debris avalanche over a million years ago; this underwater landslide likely caused tsunamis. The Hilina Slump on the island of Hawaiʻi is another potential place for a large landslide and resulting tsunami.

The city of Hilo on the Big Island has been most affected by tsunamis, where the in-rushing water is accentuated by the shape of the bay. Coastal cities have tsunami warning sirens.

A tsunami resulting from an earthquake in Chile hit the islands on February 27, 2010. It was relatively minor, but local emergency management officials utilized the latest technology and ordered evacuations in preparation for a possible major event. It was declared a "good drill" for the next major event and "a successful drill" by the Governor.

Ecology

- Related article: Endemism in the Hawaiian Islands.

The Hawaiian Islands are home to a large number of endemic species. The plant and animal life of the Hawaiian Islands developed in nearly complete isolation over about 70 million years. Mammals were absent until they arrived with the first human settlers.

Human contact, first by Polynesians, introduced new trees, plants and animals. These included voracious species such as rats and pigs, who took a heavy toll on native birds and invertebrates that evolved in the absence of such predators. The growing population also brought deforestation, forest degradation, treeless grasslands, and environmental degradation. As a result, many species which depended on forest habitats and food went extinct. As humans cleared land for farming, monocultural crop production replaced multi-species systems.

The arrival of the Europeans had a significant impact, with the promotion of large-scale single-species export agriculture and livestock grazing. This led to increased clearing of forests, and the development of towns, adding more species to list of extinct animals of the Hawaiian Islands. As of 2009, many of the remaining endemic species are considered endangered.[15]

Climate

Hawaii (state) is tropical but it experiences many different climates, depending on altitude and weather. The islands receive most rainfall from the trade winds on their north and east flanks (the windward side) as a result of orographic precipitation. Coastal areas in general and especially the south and west flanks or leeward sides, tend to be drier.

In general, the Hawaiian Islands receive most of their precipitation during the winter months (October to April). Drier conditions generally prevail from May to September, but the warmer temperatures increase the risk of hurricanes.

Temperatures at sea level generally range from highs of 85-90 °F (29-32 °C) during the summer months to 79-83 °F (26-28 °C) during the winter months. Rarely does the temperature rise above 90 °F (32 °C) or drop below 60 °F (16 °C) at lower elevations. Temperatures are lower at higher altitudes; in fact, the three highest mountains of Mauna Kea, Mauna Loa, and Haleakala often receive snowfall during the winter.

One distinctive feature of Hawaii’s climate is the small annual variation in temperature range. This is because there is only a slight variation in length of night and day from one part of Hawaii to another because all its islands lie within a narrow latitude band. The small variations in the length of the daylight period, together with the smaller annual variations in the altitude of the sun above the horizon, result in relatively small variations in the amount of incoming solar energy from one time of the year to another. The surface waters of the open ocean around Hawaii range from 77 °F (25 °C) between late February and early April, to a maximum of 83 °F (28 °C) in late September or early October. With water temperatures this mild for hundreds of miles around, the air that reaches Hawaii is neither very hot nor very cold. Temperatures of 90 °F (32 °C) and above are quite uncommon (with the exception of dry, leeward areas). In the leeward areas, temperatures may reach into the low 90’s several days during the year, but temperatures higher than these are unusual.

The other reason for the small variation in air temperature is the nearly constant flow of fresh ocean air across the islands. Just as the temperature of the ocean surface varies comparatively little from season to season, so also does the temperature of air that has moved great distances across the ocean; the air brings with it to the land the mild temperature regime characteristic of the surrounding ocean. In the central North Pacific, the trade winds represent the outflow of air from the great region of high pressure, the North Pacific High, typically located well north and east of the Hawaiian Islands. The Pacific High, and with it the trade-wind zone, moves north and south with changing angle of the sun, so that it reaches its northernmost position in the summer. This brings trade winds during the period of May through September, when they are prevalent 80 to 95 percent of the time. From October through April, the heart of the trade winds moves south of Hawaii; however, the winds still blow much of the time. They provide a system of natural year-long ventilation throughout the islands and bring mild temperatures characteristic of air that has moved great distances across tropical waters.

Winds

Island wind patterns are very complex. Though the trade winds are fairly constant, their relatively uniform air flow is distorted and disrupted by mountains, hills, and valleys. Usually winds blow upslope by day and downslope by night. Local conditions that produce occasional violent winds are not well understood. These are very localized, sometimes reaching speeds of 60 to 100 mph (97 to 160 km/h) and are best known in the settled areas of Kula and Lahaina on Maui. The Kula winds are strong downslope winds on the lower slopes of the west side of Haleakala. These winds tend to be strongest from 2,000 to 4,000 ft (610 to 1,200 m) above mean sea level. The Lahaina winds are also downslope winds, but are somewhat different. They are also called "lehua winds" after the ʻōhiʻa lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha), whose red blossoms fill the air when these strong winds blow. They issue from canyons at the base of the western Maui mountains, where steeper canyon slopes meet the more gentle piedmont slope below. These winds only occur every 8 to 12 years. They are extremely violent, with wind speeds of 80 to 100 mph (160 km/h) or more.

Cloud formation

Under trade wind conditions, there is very often a pronounced moisture discontinuity between 4,000 and 8,000 feet (1,200–2425 m). Below these heights, the air is moist; above, it is dry. The break (a large-scale feature of the Pacific High) is caused by a temperature inversion embedded in the moving trade wind air. The inversion tends to suppress the vertical movement of air and so restricts cloud development to the zone just below the inversion. The inversion is present 50 to 70 percent of the time; its height fluctuates from day to day, but it is usually between 5,000 and 7,000 feet (1,500–2,100 m). On trade wind days when the inversion is well defined, the clouds develop below these heights with only an occasional cloud top breaking through the inversion. These towering clouds form along the mountains where the incoming trade wind air converges as it moves up a valley and is forced up and over the mountains to heights of several thousand feet. On days without an inversion, the sky is almost cloudless (completely cloudless skies are extremely rare). In leeward areas well screened from the trade winds (such as the west coast of Maui), skies are clear 30 to 60 percent of the time. Windward areas tend to be cloudier during the summer, when the trade winds and associated clouds are more prevalent, while leeward areas, which are less affected by cloudy conditions associated with trade wind cloudiness, tend to be cloudier during the winter, when storm fronts pass through more frequently. On Maui, the cloudiest zones are at and just below the summits of the mountains, and at elevations of 2,000 to 4,000 ft (610 to 1,200 m) on the windward sides of Haleakala. In these locations the sky is cloudy more than 70 percent of the time. The usual clarity of the air in the high mountains is associated with the low moisture content of the air.

Precipitation

Frequent light showers fall in Hawaii. On windward coasts, many brief showers are common, not one of which is heavy enough to produce more than 0.01 in (0.25 mm) of rain. The usual run of trade wind weather yields many light showers in the lowlands, whereas torrential rains are associated with a sudden surge in the trade winds or with a major storm. Hana has had as much as 28 in (710 mm) of rain in a single 24-hour period.

Major storms occur most frequently in October through March. There may be as many as six or seven major storm events in a year. Such storms bring heavy rains and can be accompanied by strong local winds. The storms may be associated with the passage of a cold front – the leading edge of a mass of relatively cool air that is moving from west to east or from northwest to southeast.

Kona storms are features of the winter season. The name come from winds out of the "kona" or usually leeward direction. Rainfall in a well-developed Kona storm is widespread and more prolonged than in the usual cold-front storm. Kona storm rains are usually most intense in an arc, extending from south to east of the storm and well in advance of its center. Kona rains last from several hours to several days. The rains may continue steadily, but the longer lasting ones are characteristically interrupted by intervals of lighter rain or partial clearing, as well as by intense showers superimposed on the more moderate continuous, steady rain. An entire winter may pass without a single well-developed Kona storm. More often there are one or two such storms a year; sometimes four or five. Three harbors provide some protection from Kona storms: Kahului Harbor (used mostly for commercial vessels), Lahaina and Maalaea Harbors (used primarily) for sailing craft.

Hurricanes

The hurricane season in the Hawaiian Islands is roughly from June through November, when hurricanes and tropical storms are most probable in the North Pacific. These storms tend to originate off the coast of Mexico (particularly the Baja California peninsula) and track west or northwest towards the islands.

True hurricanes are very rare in Hawaii; only four have affected the islands during 63 years. Tropical storms are more frequent. These have more modest winds, below 74 mph (119 km/h). Because tropical storms resemble Kona storms, and because early records do not distinguish clearly between them, it has been difficult to estimate the average frequency of tropical storms. Every year or two a tropical storm will affect the weather in some part of the islands. Unlike cold fronts and Kona storms, hurricanes and tropical storms are most likely to occur during the last half of the year, from July through December.

As storms cross the Pacific, they tend to lose strength if they bear northward and encounter cooler water. The topography of the highest islands (Haleakalā on Maui, Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa on the Big Island) may protect these islands, because Kauaʻi has been hit more often in the last 50 years than the others.

Effect on trade winds

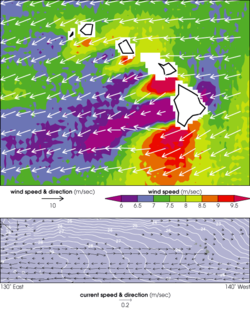

Despite being a tiny speck within the vast Pacific Ocean, the Hawaiian Islands have a surprising effect on ocean currents and circulation patterns over much of the Pacific. In the Northern Hemisphere, trade winds blow from northeast to southwest, from North and South America toward Asia, between the equator and 30 degrees north latitude. Typically, the trade winds continue across the Pacific — unless something gets in their way, like an island.

Hawaii's high mountains present a substantial obstacle to the trade winds. The elevated topography blocks the airflow, effectively splitting the trade winds in two. This split causes a zone of weak winds, called a "wind wake", on the leeward side of the islands.

Aerodynamic theory indicates that an island wind wake effect should dissipate within a few hundred kilometers and not be felt in the western Pacific. However, the wind wake caused by the Hawaiian Islands extends 1,860 miles (3,000 km), roughly 10 times longer than any other wake. The long wake testifies to the strong interaction between the atmosphere and ocean, which has strong implications for global climate research. It is also important for understanding natural climate variations, like El Niño.

There are number of reasons why this has only been observed in Hawaii. First, the ocean reacts slowly to fast-changing winds; winds must be steady to exert force on the ocean, such as the trade winds. Second, the high mountain topography provides a significant disturbance to the winds. Third, the Hawaiian Islands are large in horizontal scale, extending over four degrees in latitude. It is this active interaction between wind, ocean current, and temperature that creates this uniquely long wake west of Hawaii.

The wind wake drives an eastward "counter current" that brings warm water 5,000 miles (8,000 km) from the Asian coast. This warm water drives further changes in wind, allowing the island effect to extend far into the western Pacific. The counter current had been observed by oceanographers near the Hawaiian Islands years before the long wake was discovered, but they did not know what caused it.[17]

See also

- List of Hawaii birds

- Maritime Fur Trade

Notes

- ↑ Macdonald, Abbott, and Peterson, 1984

- ↑ James Cook and James King (1784). A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean: Undertaken, by the Command of His Majesty, for Making Discoveries in the Northern Hemisphere, to Determine the Position and Extent of the West Side of North America, Its Distance from Asia, and the Practicability of a Northern Passage to Europe : Performed Under the Direction of Captains Cook, Clerke, and Gore, in His Majesty's Ships the Resolution and Discovery, in the Years 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779, and 1780. 2. Nicol and Cadell, London. p. 222. http://books.google.com/?id=O5AqNKtDqX0C&pg=PA222.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Island of Hawaiʻi

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Maui Island

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Kahoʻolawe Island

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Lānaʻi Island

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Molokaʻi Island

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Oʻahu Island

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Kauaʻi Island

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Niʻihau Island

- ↑ "Hawai'i Facts & Figures". state web site. State of Hawaii Dept. of Business, Economic Development & Tourism. December, 2009. http://hawaii.gov/dbedt/info/economic/library/facts/Facts_and_Figures_State_and_Counties.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ "Mauna Loa Earth's Largest Volcano". Hawaiian Volcano Observatory web site. USGS. February 2006. http://wwwhvo.wr.usgs.gov/maunaloa/. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ↑ "Hawaii Earthquake History". Earthquake Hazards Program. United States Geological Survey. 1972. http://earthquake.usgs.gov/regional/states/hawaii/history.php. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ↑ "Top Earthquake States". Earthquake Hazards Program. United States Geological Survey. 2003. http://earthquake.usgs.gov/regional/states/top_states.php. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ↑ Craig R. Elevitch and Kim M. Wilkinson, ed (2000). Agroforestry Guides for Pacific Islands. Permanent Agriculture Resources. ISBN 0970254407. http://www.agroforestry.net/afg/.

- ↑ http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=3510

- ↑ Schmidt, Laurie J. (October 2, 2003). "Little Islands, Big Wake". NASA Earth Observatory. http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Study/Wake/. Retrieved 2006-05-16.

References

- Morgan, Joseph R. (1996). "Volcanic Landforms". Hawai'i: A Unique Geography. Honolulu, HI: Bess Press. ISBN 1573060216.

Further reading and resources

- An integrated information website focused on the Hawaiian Archipelago from the Pacific Region Integrated Data Enterprise (PRIDE).

- Macdonald, G. A., A. T. Abbott, and F. L. Peterson. 1984. Volcanoes in the Sea. The Geology of Hawaii, 2nd edition. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu. 517 pp.

- The Ocean Atlas of Hawai‘i - SOEST at University of Hawaiʻi.

- Introduction to Hawaiian Volcanism

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||